The Edinburgh Time Ball has been a feature of Edinburgh life, and a popular tourist sight, for over a century and a half. Charles Piazzi Smyth set up this famous time service – but when? Answering this question was trickier than I expected, and led me down a fascinating path full of intriguing historical details.

My usual source of all things to do with CPS is the wonderful book by Hermann and Mary Bruck, The Peripatetic Astronomer. They clearly state that the Ball began operation in 1852. Likewise, if you visit the Castle at One O’Clock and listen to Davie The Gunner launch into his show, he says that the Gun started in 1861 and the Time Ball started in 1852. However … our chums over at the One O’Clock Gun association say on their website that the Time Ball started in 1853… So who is right?

Digging into the archives

Piazzi Smyth’s work at the Observatory was periodically overseen by a Board of Visitors – various bigwigs appointed by the Government. The formal reports that CPS made to them are recorded as appendices to the Edinburgh Astronomical Observations (EAO) – bound volumes which we still have in the ROE archives up here on Blackford Hill. So I dug into these.

The slow progress of the Time Ball

CPS first proposes a Time Ball in his report of December 1848, arguing

… the erection of a time-ball, by which the time might be at once generally published, instead of compelling every one, as at present, to bring their chronometers all the way from Leith, for instance, would be a real boon to the public.

A sum of £200 was requested from the Government.

There had been other Time Balls before – and indeed CPS had looked after one in South Africa in the late 1830s. The idea of an Edinburgh Time Ball was approved at the meeting of April 1849. In his April 1851 report, CPS says

This matter, which was determined on by Government at the recommendation of the Board, soon after the meeting in April 1849, is, I am told, at last in a state to allow the construction of the machinery being very shortly commenced upon.

So… almost ready for action in April 1851… However, in his report of Nov 1852, CPS says

The official delays which had prevented the carrying out of the excellent intentions of Her Majesty’s Government up to April 1851, although the necessary funds had actually been voted by Parliament, have strangely and vexatiously continued to make these intentions still miscarry, even up the present time; nor have I been able to to obtain any satisfactory answers to my inquiries, as to our future prospects of seeing the erection of this very useful piece of machinery.

So what happened next?

Extending the Time service

The report to the Board of Visitors of Nov 1852, which had the brief but disappointing news that the Time Ball was still not working, appeared in EAO Volume 11, which was actually published in 1857. EAO Volume 12 finally appears in 1863, and is a bumper volume, with material about the Time Gun, and about the expedition to Tenerife. It also contains a report to the Board of Visitors from Sept 1858. Finally it seems, the Time Ball has been erected –

manufactured by Messrs Maudslay and Field, under the advice of the Astronomer Royal, Mr Airy, who gave his best assistance to the matter.

Indeed, CPS goes on to describe various possible improvements, and also an experiment relaying the time signal to Glasgow, during a meeting of the British Association. But CPS doesn’t say when Time Ball started working.

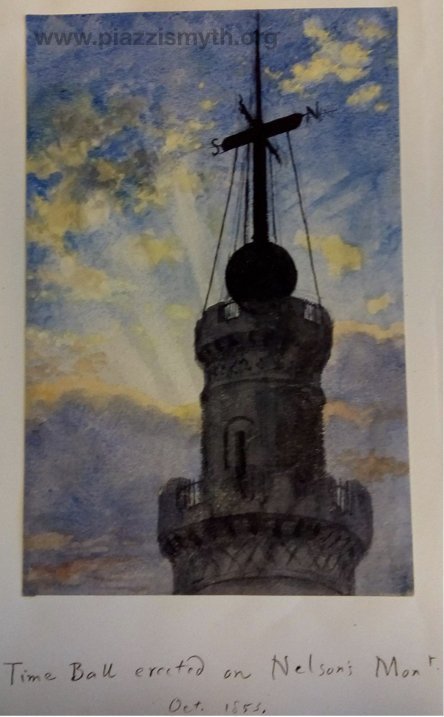

A painting of the Time Ball

So what happened between November 1852 and September 1858? Clearly, more rummaging in the archives was needed. The next clue was found in Piazzi Smyth’s own sketchbook. Here we found a very beautiful painting by CPS, clearly showing the Time Ball working, and dated October 1853. So now we have it down to a one year gap!

From ROE/RSE archives

The Scotsman to the rescue

The final clue was not in the ROE archives at all, but in the archives of the Scotsman newspaper. Bruce Vickery tracked down a short article from Nov 19th 1853 which states

We understand that the time-ball machinery, with its delicate electrical trigger, has now been completed by the engineers, and that the apparatus is so far in working order.

It is noticeable that this article appears after Piazzi Smyth’s painting mentioned above. It seems that, while the Time Ball was now working, CPS was not yet guaranteeing it as a public service.

Our best guess then is that the Ball started working pretty close in time to when CPS made his painting – October 1853. So score a goal for the One O’Clock Gun association! However… the Scotsman article is at least several weeks after the Time Ball started working – why did it take so long for people to notice? We will I think never know.

The fascination of the fall

Meanwhile, the Nov 19th Scotsman article contains a fascinating description of the fall of the Ball:

Those who, on the monument, have witnessed the fall of the ball, describe the effect as extremely interesting. The huge mass is first of all seen rushing downward with terrific velocity, as if likely to carry all before it: when suddenly, at about three-fourths down, its is brought by some invisible agent almost to a stand-still; and then, with two or three slight motions up and down, it rests on its bed-block as quietly as if nothing had happened.

I think this is still an accurate description!

For Art Buffs, you might want to know that the Scotsman goes on to report that Mr Ruskin delivered his concluding lecture on Pre-Raphaelitism the evening before in Queen Street Hall.

Trust the Public

You always find some unexpected delights when you meander through the archives. Looking for the answer to when the Time Ball started yielded a lovely example.

In his report to the Board of Visitors on April 25th 1849, Piazzi Smyth describes how, pending the construction of the proposed Time Ball, he had made arrangements for allowing the public in to see the Observatory Clock:

It had been feared that the unlimited admission of the public, without any supervision, into the interior of the building, and into immediate proximity with the clock, might induce mischievously-inclined persons to try their skill in producing troublesome derangements; and this was the reason why, in all years past, every one was excluded from entering the building and reduced to peering through the window: but as far as the experience of this year has gone, I am happy to say, that no reason has appeared to make us repent of having given these increased facilities to the public for obtaining the true time.

Who knows what mischievously inclined persons might try today, given half a chance?

Andy Lawrence, April 2019